For more than a year economists have warned that President Donald Trump’s renewed tariff agenda would unleash a new wave of inflation. Many predicted a mix of slower growth and higher prices. Some even went as far as forecasting stagflation. Yet the headline numbers tell a different story. The tariffs are in place. Import duties are among the highest the United States has imposed since the middle of the twentieth century. Companies face billions of dollars in new costs. Yet consumer prices have not surged in any dramatic fashion.

This unexpected calm has puzzled analysts and frustrated critics who assumed tariffs would feed quickly into the Consumer Price Index. But the absence of immediate price spikes is not proof that the tariffs are harmless or ineffective. Instead it reflects a mix of timing, corporate strategy, and inventory dynamics that have delayed the impact. What appears stable today may look very different once the buffers fade.

This article explains why the tariffs have not yet shown up in consumer prices, what pressures are building beneath the surface, and what realistic scenarios lie ahead for the economy in 2025.

A Policy Built on Market Gravity

Trump’s renewed tariff program was built on a simple proposition. The United States market is so large and so attractive that foreign producers would absorb most of the tariff costs in order to maintain access to American consumers. In theory this gravitational pull would allow the United States to pressure trading partners without triggering a sharp rise in domestic prices.

Most economists disagreed. Classical trade theory suggests that tariffs raise import costs. Over time those costs find their way to consumers through higher prices, thinner product variety, or lower quality. Many analysts also expected tariffs to discourage investment and slow growth. A few warned that the combination of higher costs and economic softening could produce stagflation. None of this has fully materialised in the first stretch of 2025. But the reasons are more complex than they appear.

The Front Loading Factor

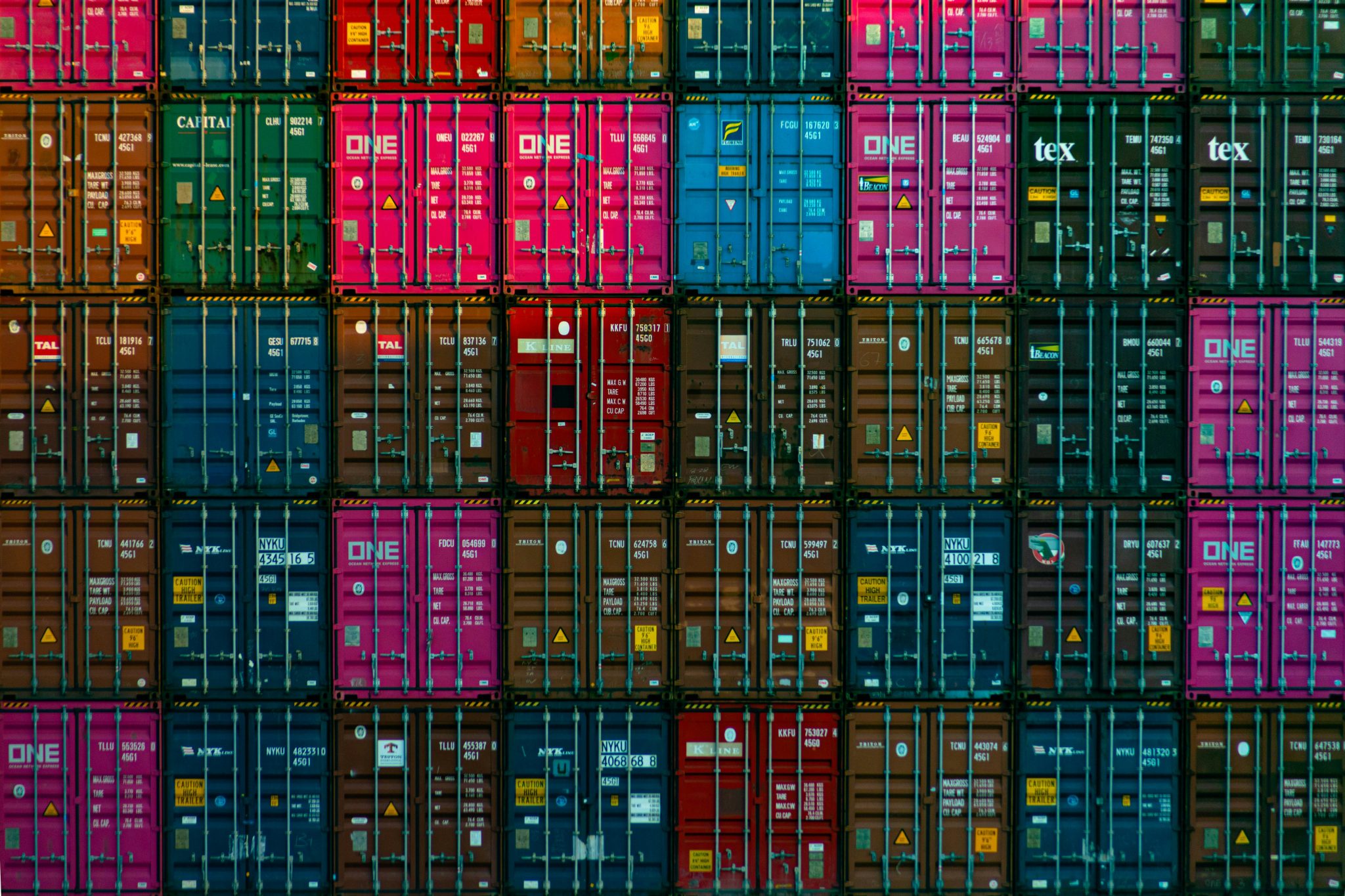

The most important explanation is that companies saw the tariffs coming. As soon as the administration signaled its intent to expand duties on goods from China and other trading partners, importers began to front load shipments. Containers poured into American ports during the final months of 2024 and the opening quarter of 2025. January imports were significantly higher than the same month in previous years and exceeded typical seasonal patterns.

Importers essentially built a protective wall of cheap inventory. Goods arrived under pre tariff price structures and can be sold throughout the year without reflecting the new costs. This stockpiling created an artificial cushion. It also inflated early 2025 economic data. Inventory accumulation contributed to stronger than expected GDP figures, giving a temporary impression of economic momentum.

This dynamic is especially visible in what supply chain analysts call the middle mile. Large volumes of imported goods are sitting in warehouses awaiting distribution. Until these inventories clear, retailers have no need to mark up prices to compensate for tariffed replacements.

Why Companies Still Hold Back

Even companies that are already facing higher input costs have been reluctant to raise prices immediately. There are two main reasons for this hesitation.

First, no firm wants to be the first mover. If one retailer or manufacturer raises prices early, customers may defect to competitors. The fear of losing market share is powerful, particularly in sectors where consumers are price sensitive, such as electronics, home appliances, and household goods.

Second, firms are navigating political uncertainty. Trump has made tariffs a central part of his economic strategy, but companies cannot be sure how long the current structure will last. A premature price hike could provoke a consumer backlash at a moment when the White House is closely monitoring corporate behaviour. Some executives openly acknowledge that they do not want to draw political attention by being seen as the first to raise prices after tariffs take effect.

There is another layer of caution. Trump’s legislative agenda includes business tax cuts designed to offset the cost burden created by the tariffs. If companies believe that fiscal relief is on the way, they may choose to absorb short term costs rather than risk losing customers.

Visible Pressure Beneath the Surface

The absence of a broad based spike in consumer prices does not mean there is no pressure building. In fact, several sectors are already feeling the strain.

Durable goods, including appliances, computers, and electronics, have recorded price increases that analysts attribute to tariff effects. Surveys of corporate financial officers suggest that more than half of American companies expect to raise prices before the end of the year. Many have already prepared consumers for adjustments.

Large brands have begun to act. Retailers and manufacturers in footwear, apparel, home improvement products, and consumer electronics have either raised prices modestly or announced increases for later in 2025. These moves have been incremental rather than sweeping, but they show that companies are gradually passing through costs as inventories thin out.

Economic research also suggests that between one third and one half of tariff related costs are already being absorbed by consumers, even if the impact remains diffuse enough to avoid dramatic changes in headline inflation. Corporate earnings reports for the first half of 2025 show margin compression in several import reliant sectors. This is an early sign that the buffers are eroding.

Small businesses are feeling the squeeze most acutely. Unlike large corporations, they lack the financial strength to absorb tariff costs for long. As a result, small firms are more likely to raise prices quickly or reduce output, hiring, or investment. The uneven burden is another warning that the full consumer impact has only been postponed.

The Unseen Drag on Growth

Hidden inside the front loading phenomenon is another risk. The surge of imports that boosted inventories in early 2025 will eventually reverse. When companies stop importing at elevated levels and begin drawing down stockpiles, GDP will feel the effect. A period of inventory depletion can become a drag on economic growth, especially if consumers reduce spending at the same time.

Slower growth and emerging price pressures can still combine into a form of mild stagflation later in the year, even if the early predictions were premature. Much depends on how quickly companies replenish inventories and how aggressively they pass along new costs.

The Scenario Ahead

Several plausible scenarios are now in play.

Scenario one. The delayed wave.

As inventories purchased at pre tariff prices run out, companies begin to pass through costs more aggressively. Inflation rises gradually but remains manageable. This is the most likely short term outcome.

Scenario two. The margin squeeze.

Firms continue absorbing more of the tariff burden in order to protect market share. Inflation stays subdued but corporate profits weaken. This scenario could weigh on investment and employment.

Scenario three. The political adjustment.

The administration introduces tax incentives or targeted relief to reduce the burden on domestic firms. This would slow the pass through to consumers but increase fiscal pressures.

Scenario four. The demand shock.

If prices rise at the same time that households face higher borrowing costs, consumer spending could soften. In this case the risk of a late 2025 slowdown becomes more pronounced.

Most analysts agree that the first scenario is the most probable. The tariffs will eventually show up in the data once the temporary buffers fade. The United States has not avoided the laws of economics. It has simply delayed them.

Conclusion

The story of Trump’s 2025 tariffs is not one of economic immunity. It is one of timing. Companies built inventory shields before the tariffs took effect. Retailers have hesitated to raise prices because they fear losing customers or provoking political backlash. Tax policies have offered partial relief. These forces have created a temporary illusion of stability.

The true test will come as the stockpiles run down. Tariff related costs are real and substantial. They are already pressuring margins and appearing in select product categories. The broader pass through is a matter of when, not if.

For now the tariff paradox remains intact. Prices appear calm. The economy looks steady. But the buffering mechanisms that have held back inflation are temporary. As 2025 progresses, the hidden impact of the tariffs is likely to move from warehouses to store shelves. Consumers, businesses, and policymakers should prepare for an economic landscape that shifts quickly once the delayed effects begin to surface.