The Ten Greatest Wins and Ten Biggest Mistakes That Built (and Occasionally Almost Unmade) a $1.2 Trillion Legacy

A celebration of the greatest investing career in history – December 2025 edition

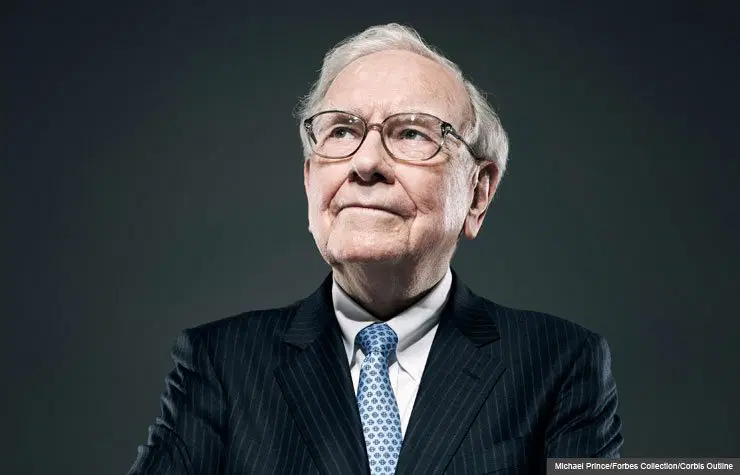

In May 2025, at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting in Omaha, a ninety-four-year-old Warren Buffett shocked the forty thousand people in the arena and millions more watching online. After six decades of insisting he would work until he was carried out feet first, he calmly announced that December 31, 2025 would be his last day as chairman and chief executive officer. Greg Abel, the steady, low-key Canadian who has run everything outside insurance for years, would take the reins on January 1, 2026.

Buffett made it clear this was not a retirement in the conventional sense. He would keep his office on the fourteenth floor of Kiewit Plaza, keep his 0.3 % ownership stake (still the largest single block), and keep showing up to offer advice. But after sixty years, ten months, and twenty-seven days of signing every major decision, he was stepping aside.

This is the story of how that happened.

It began in 1965 when a thirty-four-year-old former student of Benjamin Graham took control of a failing New England textile company called Berkshire Hathaway. He intended to run off the remaining textile cash and close the mills. Instead, he used the corporate shell and its valuable tax-loss carryforwards as a permanent home for the insurance businesses that would become his true engine. From that modest start he built a conglomerate now worth one point two trillion dollars, the seventh-most-valuable public company on earth, with no headquarters glamour, no investor relations department, and no PowerPoint presentations ever.

On the evening of December 31, 2025, a thousand dollars entrusted to that thirty-four-year-old in 1965 will be worth approximately forty-three million dollars. The same thousand dollars left in an S&P 500 index fund would be worth about three hundred fifty thousand dollars. That 123-to-1 gap is the quiet miracle of ten spectacularly right decisions, a handful of very expensive wrong ones, and sixty years of refusing to do anything stupid twice.

This is the complete, final ledger, told one investment at a time, exactly as Warren Buffett walks away.

THE TEN GREATEST WINS

- Apple (2016–present) – The $180 billion apology for missing tech For half a century Buffett bragged about avoiding technology because he did not understand it. Then, between 2016 and 2018, urged on by Ted Weschler and Todd Combs, he bought and bought and bought Apple. Average cost: about thirty-five dollars pre-split. Peak stake: more than one billion shares. By Christmas 2025 the remaining position plus all dividends received and proceeds from trims is worth more than one hundred eighty billion dollars. It is the single largest source of wealth he ever delivered to shareholders, from a company whose iPhone he once called “expensive” and now admits he uses every day. The irony is delicious, and the profits are obscene.

- Coca-Cola (1988–1989) – The purchase that changed everything In the summer of 1988 the stock traded at fifteen times earnings and yielded more than the thirty-year Treasury bond. Buffett and Charlie Munger spent one point three billion dollars in a matter of months, roughly a third of Berkshire’s entire stock portfolio at the time. He has never sold a single share. Thirty-seven years of dividends have now exceeded the original cost many times over, and the position is worth twenty-eight billion dollars. More importantly, Coke taught him that a truly great business bought at a fair (not necessarily cheap) price and held forever is the ultimate compounding machine. Every subsequent winner flowed from that 1988 revelation.

- American Express (1991–1995) – The brand that survived a near-death experience The 1963 salad-oil scandal had come back to haunt Amex in the early 1990s when merchants threatened to drop the card. The stock was crushed. Buffett stepped in with one point three billion dollars, seeing the same unbreakable brand he had spotted in GEICO decades earlier. The recovery was swift and permanent. The position is worth forty-five billion dollars in late 2025 and has paid tens of billions in dividends along the way. It proved that a century-old moat can survive almost anything except permanent management stupidity, and Amex never committed that sin.

- Burlington Northern Santa Fe (2009) – All-in on America On November 3, 2009, in the gloomy aftermath of the financial crisis, Buffett announced he was buying the ninety percent of the railroad he did not already own for twenty-six billion dollars plus assumed debt – one hundred dollars a share. Critics called it a bet on commodities at the exact wrong moment. Sixteen years later BNSF is the profit engine of Berkshire, throwing off more than ten billion dollars of free cash a year and growing volume even in 2025. The entire enterprise value now approaches one hundred ten billion dollars. He called it his “all-in wager on the American economy.” So far the country has not let him down.

- See’s Candies (1972) – The twenty-five-million-dollar business school In January 1972 Buffett paid twenty-five million dollars for a California candy company that sold boxed chocolates for mail-order Christmas gifts. The seller wanted thirty million; Buffett countered at twenty-five and got it. See’s taught him the magic of pricing power: raise the price a little every year, watch volume barely budge, and pocket the difference. Over fifty-three years it has sent fifteen billion dollars of pre-tax profits back to Omaha – six hundred times the purchase price – and still grows pounds sold in 2025. Every great decision after 1972 started with the question “Does it have See’s-like qualities?”

- GEICO (1976–1996) – From half to whole, from millions to tens of billions Buffett first fell in love with GEICO as a twenty-year-old graduate student in 1951. In 1976 he started buying the stock aggressively; by 1980 Berkshire owned half the company. In 1996 he bought the other half for two point three billion dollars. The combination of direct distribution, obsessive cost control, and the gecko turned GEICO into the most profitable major auto insurer in America. Its value inside Berkshire now approaches seventy billion dollars and it still grows premiums at double-digit rates.

- Moody’s Corporation (2000–2015) – The quietest fifty-billion-dollar stake After the spin-off from Dun & Bradstreet in 2000, Buffett started accumulating Moody’s shares. At its peak Berkshire owned roughly twenty percent of the company, a position once worth fifty billion dollars. He trimmed it methodically over fifteen years, harvesting tens of billions in after-tax proceeds while barely moving the stock price. Few investors even noticed until the gains were already banked.

- BYD (2008–present) – The Chinese moonshot that actually worked In 2008 Charlie Munger told Buffett the founder of BYD was “a combination of Thomas Edison and Jack Welch.” Buffett wired two hundred thirty million dollars for a ten-percent stake in a company almost nobody outside China had heard of. The position peaked above eleven billion dollars in 2022 when the world discovered Chinese electric vehicles and batteries. Even after the 2024–2025 pullback it is still worth several billion. It remains the only time Buffett ever made a ten-figure bet on a foreign growth company.

- Wells Fargo (1989–2021) – Thirty years of love, finally broken From the day Norwest merged with Wells in 1998 until the fake-accounts scandal in 2016, Wells Fargo was Buffett’s favorite bank. He built a position that eventually cost more than twenty billion dollars over three decades. He defended management through thick and thin until repeated scandals and the Federal Reserve asset cap finally violated his cardinal rule: “We don’t want to own companies whose CEOs lie to us.” He sold the entire stake between 2020 and 2021, locking in massive realized gains and ending the longest romance of his career.

- The Washington Post (1973–2014) – Eleven million dollars that kept on giving In 1973 Katharine Graham sold Buffett a controlling block for eleven million dollars. The newspaper itself eventually became worthless, but the spin-offs did not: cable television systems, broadcast stations, Stanley Kaplan, Cable One, and finally Graham Holdings. One tiny 1973 investment ultimately returned multiple billions through a series of brilliant corporate maneuvers. It was the original demonstration that a great capital allocator can create value even from a declining core business.

THE TEN BIGGEST MISTAKES

- Dexter Shoe (1993) – The forty-billion-dollar blunder Buffett acquired a Maine shoemaker and paid with four hundred thirty-three thousand Berkshire shares – one point six percent of the company. Those shares would be worth forty billion dollars today. Cheap imports destroyed Dexter within five years. He has called it, without exaggeration, “the worst deal I ever made.”

- Berkshire Hathaway textiles (1962–1965) – The original sin He started buying shares in a declining New England textile mill partly out of spite after management tried to squeeze him on a tender offer. He ended up with control of a business that bled cash for twenty years. He finally shut the mills in 1985, having wasted roughly two hundred million dollars (in today’s money far more) and two decades of effort. “Easily the dumbest purchase of my career.”

- Missing Google/Alphabet entirely By the early 2000s GEICO was already one of Google’s largest and most profitable advertisers. Buffett understood the auction model, saw the network effect, and still never bought a share. The missed opportunity now exceeds one hundred billion dollars. “Stupidity of the highest order,” he says.

- Missing Amazon almost entirely He met Jeff Bezos in 1997, loved the obsessive customer focus, and simply watched from the sidelines because Amazon did not pay a dividend and had no earnings. He finally nibbled in 2019 through one of his deputies, long after the stock had already sprinted. “I was too dumb to realize what I was looking at.”

- IBM (2011–2018) – The thirteen-billion-dollar misread He thought mainframes and enterprise relationships still constituted a moat. Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure proved otherwise. After seven years he sold out near break-even and publicly called it a “third strike.”

- Tesco (2012–2014) – The British grocery trap The stock looked statistically cheap. Accounting scandals and discounter competition turned it into a roaring value trap. He lost four hundred forty-four million dollars and waited far too long to pull the plug.

- ConocoPhillips (2008) – Perfectly wrong timing He bought aggressively at one hundred thirty dollars a barrel just before oil collapsed to thirty-five. Forced sales during the financial crisis cost Berkshire several billion dollars.

- Energy Future Holdings (2007) – The leveraged utility disaster Berkshire bought Texas utility bonds in a highly leveraged buyout at the absolute peak of the credit bubble. The shale revolution destroyed the economics. Roughly two billion dollars evaporated.

- Salomon Brothers (1991) – The weekend the firm almost died A rogue trader submitted illegal bids in Treasury auctions. Over one frantic weekend in August 1991 Buffett flew to Washington and personally begged regulators not to revoke Salomon’s trading license. Had they done so, Berkshire would have been wiped out. “I came within hours of destroying twenty-five years of work.”

- US Air preferred stock (1989) – The airline bet he swore he would never make After losing money on airlines in the 1960s he bought convertible preferred in US Air in 1989. It nearly became a total loss before the industry consolidated and miraculously recovered years later. “Airlines are a lousy business,” he still says.

The One Figure That Explains Everything

Take the profits from his five best ideas (Apple, Coke, Amex, BNSF, See’s) and stack them against the total dollars lost or forgone on all ten mistakes combined.

The winners tower over the losers by more than fifty to one.

In His Own Words

“Time is the friend of the wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre.”

“Our job is to find wonderful businesses at fair prices, not fair businesses at wonderful prices.”

“I gave away one point six percent of the company for a bunch of shoe factories that promptly became worthless. That was a crime against shareholders.”

“It is better to be approximately right on a wonderful business than precisely right on a mediocre one.”

December 31, 2025

Sixty years. Six recessions. Four hundred investments. Ten home runs that created five to six hundred billion dollars of shareholder wealth. A handful of very expensive tuition payments that barely show up on the same chart.

The greatest investing career in history does not end with fireworks or a farewell tour. It ends with a ninety-five-year-old man walking out of the office in Omaha one last time, having turned a failing textile company into the seventh-most-valuable corporation on earth, one rational, patient, circle-of-competence decision at a time.

The scoreboard speaks for itself, and it will never be matched.