Amidst the German island of Fehmarn’s breathtaking endless beaches, lakes, and majestic cliffs, an incredibly large underwater tunnel project is unfolding – one that will forever change the face of Europe. The island is separated from neighboring Denmark’s southern coast by a 20-kilometer stretch of water known as the Fehmarn Belt, and that’s where this megaproject is taking shape – a $7.5 billion underwater tunnel connecting the two countries.

Europe has always placed a strong emphasis on connectivity; there’s the Brenner Base Tunnel that plans to connect Austria and Italy, the Channel Tunnel that connects France and Britain, and many other projects that connect two or more European countries together. Therefore, a connection between Germany and Denmark shouldn’t seem at all far-fetched.

But, this small stretch of water between the two countries has made it near impossible to come up with a way to link them, and thwarted the plans of engineers for decades.

The Project’s Background

To understand how this underwater tunnel came to be, you need to take a look at another megaproject that’s also very important to Europe, and it’s the Øresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden. If you wanted to go to Central Europe from Sweden, you could catch a train at the Swedish city of Malmö, which would then take you to Copenhagen where you’d change onto another train to go to Hamburg in Germany.

Even on a high-speed train, this journey takes about five hours and 30 minutes, so imagine how slow it is for a freight train. This was a big deal for Sweden, since Germany is its largest export market. Which is why, while planning the Øresund Bridge with Denmark, Sweden had the brilliant idea of constructing a link at the water stretch between Denmark and Germany, and said that it’d only help build the Øresund Bridge if Denmark agreed to study building a link in the Fehmarn Belt.

Denmark agreed, mainly because this idea wasn’t anything new. In fact, there’s been talk of creating a railway between Hamburg and Copenhagen since the 19th century, but nothing really came out of that until the 1960s, when a bridge was built to cross the stretch of water between the island of Fehmarn and mainland Germany, known as Fehmarn Sound. That route was then extended to a new ferry port at Puttgarden, a village on Fehmarn island, bringing trains right up to the water’s edge. Those trains were then loaded onto ferries and carried over the Fehmarn Belt to Denmark, but the ferries were so slow and took over 45 minutes to make that trip.

After the 1960s, both Denmark and Germany talked the talk about upgrading the route to a fixed link, without actually doing anything. In fact, it wasn’t until Sweden came in that things got serious, and in 2008, the Danish and German governments signed a treaty to start work on the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link, or the Fehmarn Belt Tunnel.

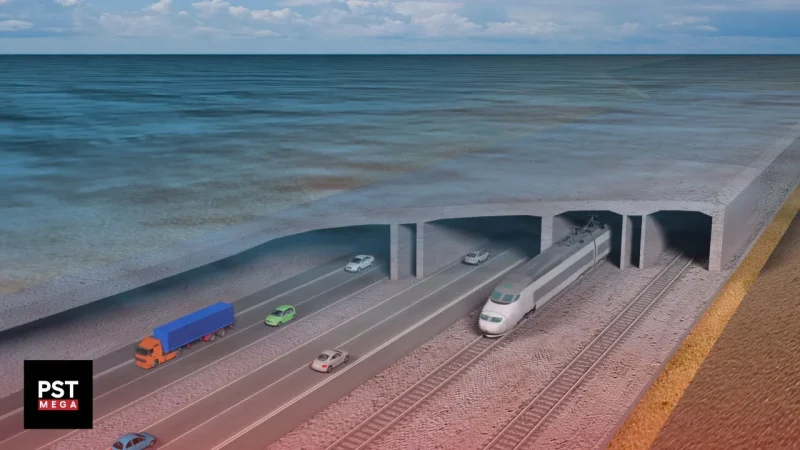

This link will consist of a four-lane motorway and two rail lines that will carry both freight trains and high-speed passenger trains, and the whole thing will be funded by Denmark, who would collect the toll fares and run the onshore businesses to recover its investment. On the other hand, Germany will upgrade the route from Fehmarn island into the mainland to allow for the new trains and traffic to pass through, and those upgrades will include digging another short tunnel across the Fehmarn Sound.

The Initial Bridge Plan

At first, the plan wasn’t to build an underwater tunnel, but a three-kilometer long, cable-stayed bridge, rising about 65 meters above the water so that ships could still pass from underneath it. It was similar to the Øresund Bridge when it came to design, but three times as long. But, this bridge just wasn’t feasible in the surrounding environment, as the Fehmarn Belt is just under 20 kilometers wide, really deep in a lot of different places, and the soil in the water isn’t fit for building a stable structure on.

Very quickly, the bridge was ruled out, and the two countries instead to go underwater rather than above it, and that’s how the idea for the Fehmarn Belt Underwater Tunnel came to be, a 160 kilometers, high-speed, low-carbon shortcut between Scandinavia and Central Europe.

Why an Underwater Tunnel?

Building a tunnel was a better idea than building a bridge overall, because a tunnel wouldn’t disturb anything above the ground, which is why tunnels are built for underground railways. Not only that, but building a bridge in Fehmarn would’ve been an ecological disaster to the island, and a tunnel is more agreeable to its delicate ecosystem.

This didn’t mean that building this tunnel didn’t come with its fair share of challenges. Tunnels like this one are dug by a tunnel boring machine, or TBM, and these machines are good for digging tunnels for underground railways because you have one track per tunnel. But, the problem is, Fehmarn needs a railway, a motorway and an access tunnel, which could mean that the construction team would need to dig five separate tunnels, and this also means five times the costs.

Another challenge is that the Fehmarn Belt is about 40 meters deep at its deepest point, and any bored tunnel would have to sit at least 10 meters below that. In simpler words, the tunnel would have to be very long in order for a train to travel into it, pass under the ocean, and emerge back up again at the other side. Therefore, it was decided that the underwater tunnel wouldn’t be a bored tunnel, but an immersed tube tunnel, or IMT.

The IMT’s Construction

IMTs are different from normal tunnels, as they are made up of prefabricated concrete elements, instead of boring through soil. Once these concrete elements are made, they’re taken out to a trench, which is dug in the seabed, then they get sealed together. When laid, the whole thing is covered over with earth, creating a tunnel.

This is a great solution for a place like the Fehmarn Belt, because it’s shallower than a bored tunnel so trains have no problems passing through, as well as being a lot cheaper to construct, and posing no risk to shipping once it’s complete. But, there’s a catch, like there always is. IMTs are usually used for fairly short water stretches like rivers, and a really long IMT is something that’s never been attempted before, but that’s what the Fehmarn Tunnel is aiming to be, but Germany and Denmark have what it takes to pull this off.

If you take a look at the construction site at Rødbyhavn on the Danish side of the Fehmarn Belt, which is so big that it took the state-owned company Femern A/S two years just to build the work area, you’d see a massive factory, which is where the tunnel segments will be constructed. This factory is one of the biggest factories ever built in Denmark, covering half a million square meters, and that large scale is needed for the production lines to produce the 89 concrete tunnel elements, each of which will be 220 meters long, 12 meters high and 40 meters wide.

During construction, aggregates and materials are delivered to the work harbor, then they get taken to the factories where the elements are being cast, and each element is so large that it’s constructed of nine smaller segments, each one taking 36 hours to cast. When one tunnel element is completed, it gets rolled out of the factory and taken to a huge dry dock where it then gets taken out to where the tunnel trench is dug. Then, ballast tanks are flooded to bring the 73,000-tonne concrete tunnel elements to the bottom of the ocean, where they are guided by winches to be within 15 millimeters of their targets.

Once all the elements are in place, the trench is back-filled and the tunnel is covered in gravel to protect it, at which point, nature takes over and eventually covers the gravel bed with sand. After that, the motorway and railway will be laid through the tunnel, and the tunnel will be fitted with ventilation, support and surveillance systems before it opens in 2029, eight years after construction started in 2021.

Benefits to Denmark

Denmark expects to benefit a lot from this project, because thousands of cars and hundreds of trains will pass through it every day, and since Denmark is going to charge cars the same amount it already charges ferries, around $100 for a return journey, this is an easy $4 billion in profit during the first 50 years of the tunnel’s life.

But, this comes at the massive price tag of $7.5 billion, with half a billion of that coming from EU subsidies, and the rest from a loan by the Danish state, meaning it won’t cost Danish taxpayers anything.

Environmental Concerns

The tunnel’s expected benefits, however, didn’t save it from immense opposition from the German AGFF action group against the Fehmarn Belt fixed link, a group that has been protesting against the tunnel for the last decade out of concerns over its environmental impacts on the German island famous for its natural scenery.

The Danish construction company behind the project said that it’s closely monitoring the environmental impacts, and that it’s using special dredging machines to minimize the effects of the construction. The company also publishes environmental data in real time on its website to improve transparency around the construction, but the AGFF is also concerned about the huge carbon footprint that will come from constructing such a massive and ambitious project, mostly from the large amounts of concrete being produced, which are 2 million tonnes according to Femern A/S’ own calculations.

But, the construction company said that it’s exerting a lot of effort to reduce that carbon footprint, and one way it’s doing this is by staying committed to using 100% renewable energy sources for the construction and operations of the tunnel.

We can say that things like this are inevitable when building large infrastructure projects like this one, and that’s what makes megaprojects so controversial. Still, this tunnel is expected to impact millions of lives across Europe, reduce transport CO2 emissions, and ease travel and trade between Germany, Denmark, and Sweden by shortening the journey from Hamburg to Copenhagen to two hours and thirty minutes, so it might all be worth it in the end once this modern engineering marvel is completed.

Disclaimer

Please visit and read our disclaimer here.