Eleven years ago, a vision was set in motion—a vision that would reshape the global economic landscape and connect nations like never before. In 2013, China unveiled its visionary plan—a massive network of infrastructure, trade, and cultural exchanges spanning continents. The Belt and Road Initiative, aimed to revive ancient Silk Road connections, fostering economic development, and enhancing connectivity on an unprecedented scale.

And over the past decade, it has done exactly that. The Belt and Road Initiative, also known as the BRI, has grown into a global force, encompassing over 150 countries with cumulative engagement surpassing $1 trillion!

It has witnessed the construction of awe-inspiring infrastructure projects. From ports to railways, highways to power plants, the BRI has reshaped landscapes, connecting distant regions and creating new opportunities for millions.

Yet, as with any ambitious endeavor, the BRI has encountered its fair share of challenges.

Since it celebrated its tenth anniversary in October of 2023, We’ll be going over some of the projects established thanks to the BRI.

Since there are so many BRI projects, it’s impossible to cover them all in one article, so we’ll focus on those completed in the first ten years of the BRI, and talk about their impact on their home countries and the total cost of each project.

By the end, we’ll talk about what the future looks like for the initiative.

Belt and Road Initiative Background

The Belt and Road Initiative is China’s strategy to connect Asia with Africa and Europe through land and maritime networks, improve regional integration, and increase global trade and economic growth.

The BRI was inspired by the Silk Road, which was an ancient network of trade routes

founded by the Han Dynasty 2,000 years ago. The Silk Road connected China with the Mediterranean Sea via Eurasia for centuries.

Now, these trade routes are established thanks to Chinese investments in the infrastructure of countries that joined the BRI, and most of these investments include building and developing roads, ports, railways, and airports. As well as power plants and telecommunication networks.

Central Asian Projects

We’re going to look at the projects region by region, beginning with an area often ignored by the rest of the world: Central Asia.

Kazakhstan

Ten years ago, the initiative was announced in Kazakhstan, a country that has been rising out of poverty for the last 20 years. The country’s poverty in 2001 was a massive 74.50% of its 15 million population.

However, during the 2000s, the country witnessed strong economic growth driven by market reforms, rich minerals and natural resources, and strong FDI. Now, its population has grown to 19 million, and only 5.2% of the population lives under the poverty line as of 2021.

The growth is evident in the country’s GDP, which amounted to $220.62 billion in 2022, almost a full $200 billion increase from the 2002 GDP of $24.64 billion.

This country is home to the first project I’ll cover, the Khorgos Gateway.

It is an overland route that’s used to transfer Chinese goods to Europe, saving more than half the time needed to transport them by sea. This project helped to boost the country’s economy and created jobs.

The construction for this project started in 2014 and was completed three years later in 2017, fully funded by the Kazakh government. But, after the project launched, Chinese company Lianyungang Port Holding Group purchased 49% of the port’s shares to integrate the project into the BRI initiative.

China later invested $76 million to develop the project, which cost $239 million.

Kyrgyzstan

This country has suffered from political instability for years since its independence from the USSR in 1991, leading to the overthrow of presidents in 2005, 2010, and, most recently, 2020. However, the political situation stabilized in 2021, and the presidential form of the government was consolidated.

Due to its political issues, economic growth has been slow in the country. Its population in 2000 was 4.898 million, and the poverty rate was 95.20%. In addition, the GDP for that year was $1.37 billion, a decrease of around 47% from the $2.57 billion GDP it had under the USSR occupation.

Kyrgyzstan recorded a population of 6.6 million in 2021, and the poverty rate for the same year was 33.3%. The Kyrgyz Republic’s GDP for 2022 was $10.93 billion.

Over the past ten years, the principal investor in Kyrgyzstan has been China. In fact, 33% of foreign investment has been from China because China aims to build a better view of itself for Central Asian countries. In addition to these investments, many Kyrgyz citizens are offered scholarships through the Confucius Institute to study Chinese or live in China.

One of the major projects in the country born out of the BRI program is the Datka-Kemin power transmission line, built to increase power generation in the country and save millions in transit fees. The project cost $390 million.

Other vital projects included a cement plant and an oil refinery in Osh Oblast, costing $10 million and $60 million, respectively.

The projects created job opportunities for the locals, but they weren’t significant, amounting to only 0.1%-0.3% of total employment in the country. In addition to that, the construction work enhanced nationalism in Kyrgyzstan as the locals protested over Chinese construction workers getting paid more while doing the same work as local construction workers.

In 2021, China’s investment in Kyrgyzstan amounted to $335 million, a 146% increase from 2020.

Uzbekistan

The country has seen rapid economic and social reforms in recent years, and poverty is on the decline. It recorded a population of 34.92 million in 2021, with 17% living under the poverty line.

This country was also under the rule of the USSR and gained independence in 1991. Its population then was 20.95 million, and it recorded a poverty rate of 95.50% seven years later in 1998.

Comparing the country’s GDP throughout the years, it grew from $13.68 billion in 1991, when it gained its independence, to 80.4 billion in 2022.

BRI projects in this country include a cement factory that will increase industrial production in the district by five times and employ 750 people. The final products will be supplied to markets domestically, along with $20 million worth of materials that will be exported annually. The cost of the first stage of the project was $203.9 million, and the second stage was $215 million.

A modern hub for exporting agricultural products for processing fruits, vegetables, meat, and dairy products was also established in the Bukhara region for the cost of $28.7 million.

Another project is the development of the Mingbulak oilfield, to increase the oil production to 40,000 barrels per day. This cost $211.7 million. After this project was finished in 2019, the field hit peak production a year later in 2020.

Tajikistan

This country experienced impressive economic performance over the past decade, with its GDP increasing from $7.633 billion in 2012 to 10.5 billion in 2022.

The country’s strong growth allowed it to introduce higher wages, which in turn led to reducing poverty from 32% of the population in 2009 to 12.4% in 2022. The population for these years was 7.325 million and 10 million, respectively.

China participated in the development of the Bokhtar Oil and Gas Field, paying $80 million. There’s also the construction of the Vanj River Bridge, the most important bridge of the Tajikistan-China Highway Project, as it ensures the smooth transport of goods in Central Asia. The bridge’s cost was $9 million.

Generally, Tajikistan has 44 projects in which China has invested, and the BRI’s investment in roads and infrastructure helped insert the country into more robust trade with China and Europe. This is reflected in GDP growing by 8% in 2022, and the growth forecast for 2023% is 6.5%.

Southeast Asian Projects

The region we’ll talk about now is becoming one of the fastest growing in the world. Because of that, China is seeking to strengthen its ties with South and Southeast Asia like many other countries in the world.

Indonesia

We’ll start this region with Indonesia, the country with the largest economy in Southeast Asia. The country’s population is nearly 280 million, and it made massive gains in poverty reduction, cutting the poverty rate by more than half since 1999, when its population was 210 million. Its 1999 poverty rate was 27.13%, and in 2022 it decreased to 9.5%.

In addition to that, Indonesia recorded a GDP of 1.32 trillion in 2022.

This country is home to one of the most significant projects under the BRI: The Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Railway project. The railway was built to cut the time spent traveling between the two cities from over three hours to around 40 minutes. It was opened in 2023 after a delay and cost China $4.5 billion. Indonesia is expected to earn approximately $18 billion from developing towns around the railway line.

Another project is the Morowali Industrial Park, which helped Indonesia become the world’s second-largest stainless steel producer, producing 3 million tons annually. The overall cost for this project was $18 billion.

China has also invested in other industrial parks, power plants, and tourism facilities in Indonesia and will continue to do so. Just last year, Indonesia was the third-largest recipient country of Chinese investments, with $560 million.

Laos

Moving on to Laos, a country that has been struggling for the past three years because of the effects of the pandemic. Covid-19’s impacts on Laos’ economy include a surge in inflation and a weakened currency. It recorded a population of 7.1 million in 2018, with 18.3% living under the national poverty line.

Its GDP for 2018 was $18.14 billion. Still, it began rapidly declining during the country’s economic crisis caused by the pandemic, reaching $15.72 billion in 2022, and leaving the country fearing defaulting on its debts, including the cost of this upcoming project.

The most well-known BRI project in Laos is the China-Laos Railway. The railway connects southern China with Laos’ capital, Vientiane. The railway increased the number of passengers by 256.2%, and the number of transported goods by 320%. It also saved commuting time. This project cost $6 billion and was criticized by the Laotians, as many were displaced during the construction and felt they weren’t compensated fairly. There were also concerns about using underground minerals in Laos as loan guarantees.

Malaysia

This country is considered one of the most open countries in the world, with a trade-to-GDP ratio averaging over 130% since 2010. Malaysia, whose openness to trade helped its economy grow from $100 billion to $406 billion in twenty years, from 2002 to 2022.

Malaysia recorded a population of nearly 34 million in 2022, of which 6.2% live under the national poverty line.

Malaysia signed multiple investment agreements with China, including the East Coast Rail Link. This project’s original cost was $27 billion, and it was agreed on by Malaysia’s former Prime Minister Nagib Razak in 2016.

However, during the 2018 elections, parties opposed to Razak vocally disapproved of Chinese investments in Malaysia and expressed concerns over indebting Malaysia to China. After the elections, the project was canceled. However, after months of negotiation, the two countries agreed to get the project back on track in 2019, with a reduced budget of $10.68 billion. The project is now 52.9% done and is expected to be entirely finished by 2026. It is supposed to boost Malaysia’s economy by linking cities and ports to increase trade, foreign investment, and tourism.

Another controversial BRI project in Malaysia is the Forest City in Johor. The plan was to develop this project with $100 billion from the Chinese developer Country Garden. The company was still trying to prevent defaulting on its debt when it invested $4.3 billion seven years into the project. Development is still in progress, but the city is a ghost town, housing only 1% of its target population – around 10,000 people. The project was also criticized because many natural habitats were destroyed during construction, and it was called the world’s most useless mega-project.

In October of 2023, Country Garden defaulted on its debts, raising concerns over the future of Forest City and whether it’ll be sold to creditors over this issue.

The Maldives

This country saw robust economic growth throughout the years due to its strong tourism sector, contributing more than 28% of GDP and 60% of foreign exchange.

Despite having a small population of around 550,000 people, the Maldives’ GDP grew by 12.3% in 2022, reaching 6.19 billion. In 2019, 5.4% of the population was living under the national poverty line.

China invested in the Maldives’ infrastructure and funded projects such as Sinamale Bridge, which links the Male and Hulhule islands and makes it easier for tourists and locals to cross between them. It brought business opportunities to locals by reducing the travel time between the islands and costing $200 million. The general public criticized the high cost.

Another project in the Maldives was the expansion of the Velana International Airport; this was needed to meet the projected increase in passenger numbers, which is 7.3 million by 2030. The project cost $800 million.

There’s also the China Link Road, built to connect four islands in the Maldives. The project was identified as a special economic zone at first, but no development work has started in it so far. Its estimated costs were around $26 million.

The president of the Maldives welcomes more Chinese support and believes that the Sinamale Bridge is the most iconic and transformational project carried out so far in the country.

Thailand

This is a country that managed to move from a low-income to an upper middle-income country in less than 20 years. Its GDP in 2022 was $495.34 billion, growing annually by around 2.6%.

Thailand has a population of around 71 million; in 2021, 6.1% lived under the poverty line.

China and Thailand share a vision of establishing Thailand as a transportation hub for the region and strengthening the connection between China, Thailand, and other ASEAN countries. This is why Chinese investors were invited to invest in the Thai Land Bridge project, which is expected to cost nearly $28 billion.

The purpose of the bridge is to link trade routes between the East and the West, and it is expected to increase southern Thailand’s contribution to annual GDP to about 10%, from 2% currently, for ten years. The project would also create 280,000 job opportunities in the southern Thai provinces Ranong and Chumphon and cause a growth of 5.5% for the country’s economy, compared to 2023 growth, which is estimated to be from 2.5% to 3.0%.

The government also announced that it will start receiving money from investors for the project in 2025, and construction will begin the same year. The first phase of the bridge will be completed in 2030 and the last in 2039. By the end of this period, both ports linked by the bridge should be able to handle 20 million cargo containers on an annual basis.

South Asian Projects

Pakistan

Moving on to South Asia’s second-largest country and longtime ally of China, Pakistan. It recorded a GDP of $376.53 billion in 2022. The country is facing a considerable poverty problem, with 40% of its nearly 242 million people living under the poverty line.

Chinese investments in Pakistan are driven by the development of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a Chinese infrastructure network project in Pakistan. This project became an essential part of the BRI.

Massive BRI infrastructure projects in Pakistan include developing the already existing Gwadar Port. The Zhuhai Port Holdings Group received $1.02 billion from the state-owned China Overseas Port Holding Co. to develop the port in 2013. This investment was used to recover and upgrade port operations, including five new container bridge cranes, a new 100,000m2 storage yard, and seawater desalination equipment. This helped the port by increasing its shipping volume for international trade.

The Chinese company aims to build Gwadar into an intelligent port city by 2050, with a population of more than 1.7 million and an annual GDP of $30 billion.

Another ongoing Gwadar project is the New Gwadar International Airport, which is expected to cost $246 million and is fully funded by China. These projects aim to provide Pakistan with a means of development it desperately needs and to provide China with an easy way to transport goods in the Indian Ocean.

Finally, the Sahiwal Coal Power Project cost $1.91 billion, and construction began in 2015. When this project is completed, the power generated from it will be sold to the government of Pakistan under a 30-year purchase agreement.

Sri Lanka

This country is currently going through its worst economic crisis in decades. Its GDP in 2022 was $74.4 billion, declining from $89.01 billion in 2019 due to the pandemic, unsustainable debt, and a severe balance of payments crisis. For 2023, its GDP is expected to fall by a further 4.2%.

China’s leading investment in Sri Lanka is the Hambantota International Port. It was funded mainly by the Chinese government, which lent Sri Lanka more than $1 billion. The port should’ve been thriving with its strategic location near many of the Indian Ocean’s shipping routes. Still, it didn’t make a profit, and the Sri Lankan government ended up defaulting on its debts to China, which led to China taking over the port on a 99-year lease.

The new Chinese management focused more on developing the port’s operations, sensing that the reason why the port wasn’t profitable under Sri Lankan management.

The operational investment and knowledge simply weren’t enough. Evidence for this is shown in the port’s 2016 revenue of $11.8 million, accompanied by expenses of $10 million as direct & administrative costs. This made the operating profit for the year only $1.81 million.

These events are often quoted by critics of the BRI, saying it’s a strategy meant to increase China’s influence by exploiting developing countries and pushing them into debt traps. Now that Sri Lanka faces political issues and bankruptcy, critics worry that China might use the port for military reasons.

African Projects

This is a continent in which many countries enjoy good relations with China, supporting China’s endeavor for national unification.

Djibouti

Starting with one of the smallest countries in Africa, with only 23,200 square kilometers and a population of a million people, of which more than 23% live in extreme poverty. This country is Djibouti. In 2022, Djibouti recorded a GDP of $3.52 billion, with an annual growth of 3%.

In 2018, Djibouti commissioned a $3.5 billion free-trade zone from China to deepen its ties with China and create many job opportunities for the youth. This trade zone is going to be the largest in Africa, and it will allow investors to conduct their operations without paying some types of taxes, such as income, property, and value-added taxes. The final project will be finished by 2028, and it’s expected to be able to handle trade worth $7 billion and create 15,000 jobs once it’s completed.

In the same year, the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway was opened. This railway line linked the capital of Ethiopia and the Djibouti port. It is the first-ever electrified railway in Africa and a milestone project under the BRI. The Exim Bank of China loaned Djibouti and Ethiopia nearly $3 billion for the project, and it was a success. As of June 2022, transportation income grew 35% in annual terms since the project’s launch, and revenue from freight transportation grew 9.3%.

In 2019, Djibouti opened another project funded by China, the Doraleh Multipurpose Port. This port was completed at the cost of $590 million and was founded as an extension of the existing Djibouti port to connect Africa with Asia and Europe.

However, Djibouti’s dependence on Chinese investment could force the country into a corner. At the beginning of 2023, Djibouti struggled with inflation and drought, so it suspended its debt payments to China. This is a precarious situation for the country, whose debts account for around 80% of its GDP.

Egypt

Moving on to Egypt, the country with the second largest economy in Africa, with a GDP of $476.75 billion in 2022. Egypt experienced various economic shocks due to the pandemic, the Russian-Ukrainian war, and Middle-Eastern conflicts, resulting in a rapid increase in inflation and prices, with more than 32% of its 110 million people living under the national poverty line.

Thanks to the good relations it enjoyed with China for years, Egypt was one of the first countries to join the BRI. China invested in the development of the Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone (SETC-Zone), which was established in 2008. The SETC-Zone boasts more than 100 Chinese companies and more than $2.5 billion in sales. This project perfectly serves the BRI due to its location and logistical capabilities.

China also backed multiple infrastructure investments in Egypt. The biggest of all is Egypt’s Iconic Tower in the New Administrative Capital, in which China invested $15 billion. The new capital was designed to move government headquarters away from Egypt’s capital, Cairo, to relieve the extreme traffic in the city.

These megaprojects increased Egypt’s foreign debt, which reached $164.7 billion in June 2023, and they aren’t generating enough foreign exchange, leaving Egypt still waiting for capital inflows.

Algeria

This country’s economy is centered on hydrocarbon production and export revenues. Its 2022 GDP was $191.91 billion.

Algeria has a population of nearly 45 million people, who are greatly affected by the inflation in the country, which reached 9.72% in 2022. As of 2021, almost two million Algerians live in poverty.

Algeria is home to a massive yet often ignored BRI project: the Cherchell Ring Expressway & Port project, which China partly funds. This project is an extension of the Bou-Ismail-Cherchell Expressway, and it’s designed to link the Mediterranean with deeper parts of Africa, as it connects Algeria to Nigeria, Niger, and Chad, introducing trade to a combined market of about 275 million people.

China put in $3.3 billion for the redevelopment of the port, and the project will be completed by 2024. The Algerian government is optimistic about the project, revealing in a forecast that the port is expected to be able to handle processing 30 million goods annually by 2050.

Ethiopia

This country has one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa, with an annual growth of 5.3% in 2022. It even recorded a GDP of 126.78 billion in the same year.

It is also the second most populous country in Africa, with a population of around 120 million people. Despite its growing economy, it’s still a poor country with a per capita gross national income of $1,020 in 2022.

In addition to the Addis-Ababa to Djibouti Railway, China funded other projects in Ethiopia. For example, the Ethiopian Eastern Industrial Zone was established in 2007. It cost $180 million and was added to the BRI years later. The industrial zone created 20,000 jobs.

China built many other industrial parks in Ethiopia, and the economy of the African country is now growing at an average rate of 10% annually due to BRI contributions.

Kenya

This country made significant political and economic reforms, and reported a GDP of $113.42 billion in 2022, with an annual growth of 4.8%.

However, it’s still plagued by issues such as poverty, inequality, unemployment, and climate change. In Kenya, nearly 2.6 million people fall into poverty or stay poor due to illnesses each year.

The BRI’s project in Kenya is the country’s biggest since it gained its independence from British colonization. It’s the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway.

In 2014, Kenya secured a $3.2 billion loan from China to build the railway that connects the Mombasa port with the capital city, Nairobi. The plan was also to link the railway with other East African countries, like Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Burundi.

The first section of the railway was opened in 2017, but Chinese funds stopped coming in two years later, undoing the plans to connect Kenya to East African countries with the railway.

This might be the reason why the railway isn’t making any profits from transporting commodities for trade, and economists in Kenya are questioning whether the country can pay back the money.

The losses were evident immediately after the railway began its operations as the railway made a loss of $90.3 million in its first year, and even though the government then predicted a profit of $46.8 million in the next year, the railway kept losing money, making losses of $200 million over three years.

Despite offering passenger services that are quite successful as Kenyans prefer to use the railway over buses for their commutes, the main reason behind the project was to increase freight and exports, but this didn’t happen as traders realized it cost more to transport goods using the railway rather than trucks, the railway was used more for imports. The growth in Kenya’s GDP that was promised by the government when the project was announced didn’t materialize.

Mozambique

This country is considered one of the poorest countries in the world, with more than 46% of its 33 million people population living in poverty.

Even though Mozambique experienced economic growth in recent years, recording a GDP of $17.85 billion in 2022, access to nutritious food, clean water, sanitation, electricity, and employment is still low, especially for those in rural areas.

This is particularly impactful because about two-thirds of its population live and work in these rural areas.

Mozambique is home to Africa’s longest suspension bridge, the Maputo-Katembe Bridge. The bridge cost $726 million dollars, of which China funded 85%. Construction started in 2014 and finished four years later. The two cities the bridge links, Maputo and Katembe, have populations of 2,000,000 and 20,000, respectively, and the point of the bridge is to help grow the population in Katembe, with a forecast of growth by 400,000 people.

Like many other BRI projects in Africa, this project received its share of criticism due to the displacements of locals during construction, and many workers went on strike because of poor working conditions and late salary payments.

Nigeria

This country has Africa’s largest economy. It recorded a GDP of $477.39 billion in 2022, but its economic growth has been slow, growing by only 3.3% in 2022.

The country is also the most populous African country, with nearly 225 million people. It also has a massive poverty problem, with around 88.4 million living in extreme poverty as of 2022.

One of the BRI projects in Nigeria is the Abuja-Kaduna rail line. It is one of the first standard gauge railway modernization projects undertaken in the country, and it cost a total of $876 million, $500 million of which was invested by China. Construction began in 2011 and ended in 2014 with China’s support.

The railway project was profitable until a terrorist attack on the rail line in 2022. The attack caused the deaths of eight passengers, and many others were held for ransom by the terrorists. Following the attack, revenues dropped significantly after the trains resumed operations. The railway earned around N500 million ($635,000) monthly before the attack, and after the attack, it recorded a profit of just N1 million ($1,270) in August of 2023.

Uganda

This country is experiencing rapid economic growth right now, recording a GDP of $45.56 billion in 2022, a $5 billion increase from the previous year.

Its population in 2023 reached 49 million people, of which 41.7% live in poverty. However, accelerating economic growth in the country could reduce that number to 40.7% by 2025.

In Uganda, China financed two major hydroelectricity projects. They are the Karuma Hydroelectric Power Station and the Isimba Hydroelectric Power Station. Both projects were 85% funded by China, with construction costs of $1.7 billion and $567.7 million, respectively. The Karuma station’s construction started in 2013 and is yet to be finished.

However, the construction for the Isimba one was completed in 2019, taking four years after it began in 2015. Thanks to this project, Uganda’s state-owned Uganda Electricity Generation Company recorded a 24% growth in income in June of 2022, attributing it to the sales of electricity generated by the Isimba station.

This didn’t last for long, because the Isimba dam was flooded in August of 2022, and the operations in the power station were shut down, causing country-wide blackouts. Currently, the government is conducting independent investigations to identify severe defects in the station.

Latin American Projects

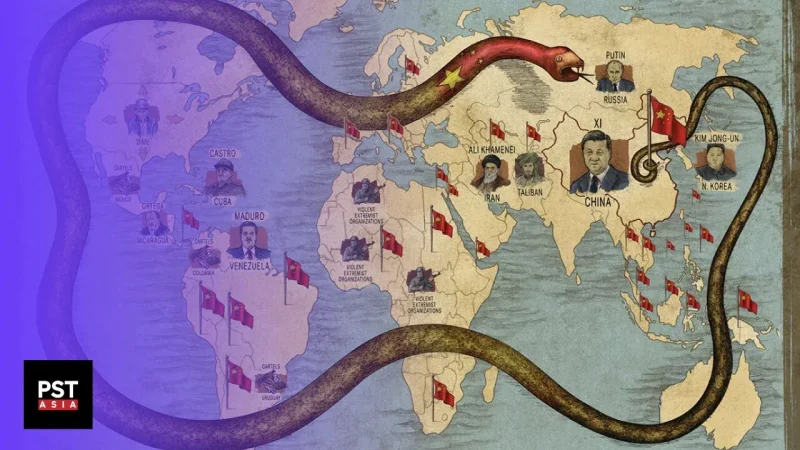

The final region we’ll talk about is Latin America, where China is constantly trying to increase its presence through trade and strengthening its military ties with several countries in the South American continent.

Peru

The most important BRI project in Latin America is in Peru, which made remarkable economic progress in the past two decades. Still, the growth slowed down after the pandemic.

It recorded a GDP of $242.63 billion in 2022, and an annual growth of 2.7%.

Peru has a population of around 34 million people, and they were greatly affected by the pandemic, with nearly two million people becoming poor because of it. As of 2023, seven in ten Peruvians are poor or are at risk of falling into poverty.

The country needs the Chancay multipurpose port terminal, the BRI’s most ambitious port project, which is meant to contribute so much to international trade as the link between Latin America and Asia. The $1.3 billion project will offer a direct route to China from Peru, reducing the ships’ traveling time by ten days when they usually take more than 45 days for the journey while having to stop at Mexico and the United States.

The project’s first phase is expected to be completed in 2024, and to provide 10,000 new jobs for locals. It comes at a perfect time, as Peru’s free-trade agreement with China is in the process of being optimized.

It’s no surprise that many American critics of the project are questioning China’s real motive behind building a port in South America, explaining that the port is just China’s way into establishing a base and increasing its influence in the Americas in order to gather intelligence on the United States.

And it’s not only American critics who are angry with the project; several Peru locals who live in Peralvillo, a town near the construction site, lost their homes and had their streets destroyed due to a construction accident. The town’s inhabitants were fearful for their safety, and the Chinese company behind the construction was forced to stop it in August.

What’s next for the Belt and Road Initiative?

After a decade of large-scale infrastructure investments in many parts of the world, things definitely changed for China.

China’s vision for the BRI’s future is to invest in smaller, less risky projects. Evidence for this is shown in the Kenyan Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway, for which China suddenly withheld funds. Many developing countries that borrowed money from China experienced harsh economic downturns during the pandemic; some haven’t recovered yet. A decade after the launch of the initiative, 60% of China’s loans to other countries are held by countries in financial distress, compared with only 5% in 2010.

This caused China to rethink its ambitious program, with Chinese banks fearing risks of default, especially in Africa, where Chinese investments significantly dropped from $8.5 billion in 2019 to $1 billion this year.

So, will Chinese infrastructure investments be a thing of the past in the future? Absolutely not. The things that changed are the size of the projects, and the amount of money Chinese banks are willing to invest. The strategy now targets sectors such as green energy, 5G technology, and healthcare for small investments to minimize the risks of bad debts and default.

Even if the initiative’s economic goals weren’t exactly achieved, we can’t say the same for its geopolitical goals.

More than 150 countries, accounting for 40% of the world’s GDPs and two-thirds of the world’s population, have signed BRI agreements with China. Xi Jinping wanted the BRI to push the image of a more assertive China, and this is evident in the fact that the country’s overseas loans are equal to a quarter of its GDP, allowing China to have geopolitical leverage over the countries it gives loans to.

China can use its status as one of the world’s largest creditors to get out from political issues, such as the country’s treatment of the Uyghurs or the constant pressure it puts on Taiwan. A good example of this is Nicaragua only being allowed to join the BRI after cutting ties with Taiwan in 2022.

So, the impact of the initiative can’t be denied, not even by the West. In 2021, American President Joe Biden launched the Build Back Better World Initiative (B3W) in a G7 meeting, an infrastructure investment program meant to counter the BRI. Still, it lacked the same level of funding. In 2022, investments under the Western initiative equaled only $6 million, so it isn’t seen as competition by China.

In fact, it seems that Chinese banks are only worried about debt sustainability issues, leading us to believe that the future of the program depends on China’s ability to deal with debt sustainability and its ongoing slowing economy. However, it still has the potential to impact the economies of many countries positively.

Disclaimer

Please visit and read our disclaimer here.