Laos, a country in Southeast Asia, is on the brink of total economic collapse. The country’s economic crisis has been going on for years, and its problems were made worse by the pandemic, soaring inflation, and public debt.

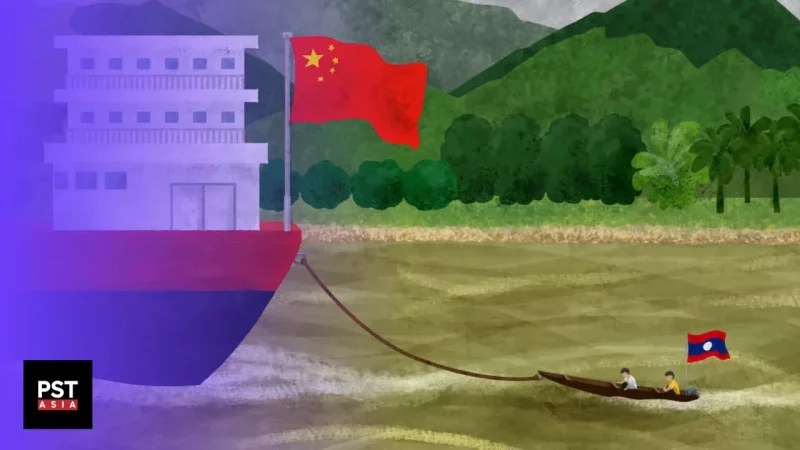

What’s even more shocking than gross government debt reaching 123% of its GDP is the fact that more than half of it is owed to Laos’ long-time ally – China. Due to massive infrastructure projects usually associated with the Belt and Road Initiative, Laos has become heavily indebted to China, causing some to question whether the BRI has been a blessing or a curse for Laos.

Is Laos caught in a Chinese debt trap…or is it the other way around? Has Laos instead ensnared China in a creditor trap?

Laos History

Many of you probably have never heard of Laos until now. After all, it’s a small country with a population of around 7.6 million. It isn’t really known for exporting anything very important, as its main exports are wood, coffee and clothes.

Laos, or officially the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia. It is known for its mountainous terrain, ancient cultures, waterfalls, jungles, Buddhist monasteries, and for its French colonial architecture.

Laos was a French colony for 60 years before gaining independence in 1953 after getting caught up in the Vietnam War. During this time a power struggle emerged between its communist forces and royalists leading the communist forces to overthrow the monarchy in 1975.

After this it became very reliant on the Soviet Union until the USSR’s collapse in 1991. Today, this country is on the brink of economic collapse, raising concerns over Laos’ debts and obligations to its largest creditor — China.

China became the largest investor in Laos in 2013 thanks to the Belt and Road Initiative, and by 2021, its accumulative investments in the Southeast Asian country reached $16 billion. Now Laos finds itself dependent on China in the same way it was dependent on the Soviet Union in the past. According to the IMF, Laos’ public debt accounts for 123% of its GDP as of this year, with more than half of that owed to China.

Now some are wondering whether Laos is caught in a Chinese debt trap…or is it the other way around? Has Laos instead ensnared China in a creditor trap? To understand who should blame who, we have to go back to the start of Laos’ reliance on China – the Belt and Road Initiative.

Laos & the Belt and Road Initiative

As part of the BRI, Laos borrowed billions of dollars from China to fund railways, highways and hydroelectric dams. But the biggest BRI project in Laos was the $6 billion China-Laos Railway which runs between the Chinese commercial hub of Kunming and Laos’ capital Vientiane.

Built to Chinese rail standards, this project turned a two-day journey across the country into an extremely fast three-hour trip. The railway increased the number of passengers by 256.2%, and the number of transported goods by 320%. It also saved commuting time and boosted tourism in the country. In just the first half of the year, the country welcomed 1.6 million foreign tourists, compared to only 42,197 a year ago. But the railroad has also brought hardship with it also.

The project was extremely controversial, since the Lao government’s share in it is only 30%, while China holds the other 70%. More concerns were raised when Laos agreed to provide “underground mineral reserves” as collateral, allowing China to extract minerals from Laos in the case of default.

With just a 30% stake in its most expensive infrastructure project, Laos is now struggling to pay back its debts, leaving many fearing that Laos is stuck in a debt trap like what happened with Sri Lanka.

These concerns were heightened when Laos handed a Chinese-owned company a 25-year concession to manage large parts of the state-owned energy company Électricité du Laos in 2021, including control over exports, paralleling Sri Lanka giving a Chinese company a 99-year lease on the Hambantota Port in 2017 because it couldn’t pay back the funds it took to develop it.

While this railroad has no doubt helped push Laos to the brink of economic collapse, the story of how it reached this crisis actually begins much earlier with the governments’ plan to build dams along the banks of the Mekong River in the early 2000s.

Laos Hydroelectric Dams

When the Soviet Union fell, Laos began to open up more, especially to its Southeast Asian neighbors. In 1996, Laos applied for ASEAN membership, and was accepted as a member a year later.

Then Laos applied various economic reforms that decentralized government control and encouraged the establishment of private companies along with state-owned firms. Its efforts paid off when it witnessed consistent economic growth afterwards, and ranked among the fastest growing economies in the world, with an average GDP growth of nearly 8% a year in 2007.

Despite all of this, Laos is still considered one of the poorest countries in the world. So, why is that the case?

The growth in Laos’ economy was mainly due to large investments in capital intensive sectors, such as hydropower and mining. Laos’ government revealed a plan to build hundreds of dams along the Mekong river for generating hydropower, dubbing itself the ‘Battery of Southeast Asia’. But this came at a huge cost.

Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia share the Mekong river with Laos, and expressed concerns over the environmental impacts of the extensive dam-building.

They had every reason to worry, as the Lao government showed very little care when it came to conducting environmental and social impact assessments of its projects, and unfortunately, it’s the Lao people who paid the price.

You should know that the megaprojects announced by the government completely failed to create jobs in the country. Despite building 78 dams, 80% of the population still lives in rural areas and work in farming or fishing to survive.

Construction on these dams also destroyed many Laotian farmers’ lands forcing them to move away. Meanwhile fishermen’s livelihoods were threatened by the dam-building that prevented fish from reaching their boats.

Clearly the lack of proper assessments for these projects have had disastrous consequences. One of which was the Attapeu dam collapse in 2018, killing at least 71 people and displacing 7,000 others. Although the government has paused some of its dam building projects, it has signed memorandums of understanding to build another 246. Considering how little the previous 78 dams benefited the country, it’s hard to see how 200 more will change things in Laos.

Setting the reckless dam projects aside, there still may have been a chance for Laos to have recovered from this disastrous project if the government’s investment in these megaprojects hadn’t been mostly financed by foreign debt.

The Economic Crisis

Laos’ macroeconomic stability was threatened by this short-sighted decision, but the country’s vulnerabilities that had been building since the Soviet Union’s collapse were suddenly exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

As a result, the country’s economic growth slowed to 0.5% in 2020 and 2.5% in 2021. The national currency, the kip, also depreciated significantly against the U.S. dollar. Now one dollar is worth around 20,000 kip, a 150% increase since 2019 before the pandemic.

It got even worse in 2022 as inflation started to skyrocket, increasing the prices of everyday goods and causing many people to fall into poverty. Now the country’s inflation rate hovers around 25%, after it peaked at 41.3% in February of this year.

As you can imagine, the country’s youth have lost their faith in the government. In fact, 38.7% of 18-to-24-year olds are not in education, employment or training, the highest rate in all of Southeast Asia.

In response to the economic instability, the government has implemented several measures to try to reduce inflation and stabilize the economy, including interest rate increases, bond issuances, and working with the Asian Development Bank on debt management practices.

The country’s central bank even made a bold claim that inflation will drop to 9% or lower by the end of 2024 just by ensuring that the income earned from exports enters the banking system. But it’s not just Laos trying to bring back economic stability to the country, China is as well.

Laos’ Credit Trap

China is unwilling to let Laos default for multiple reasons, including that Chinese banks don’t want to be burdened with bad assets, and that in the case of Laos defaulting, China would look like an unreliable lender to the rest of the BRI countries. In addition to that, strong relations between China and Laos help China’s position in Southeast Asia, where opinions of it are generally mixed.

That’s why from 2020 to 2022, China gave Laos significant short-term debt relief. So much so that the World Bank estimated the deferred repayments over those three years reached about 8% of Laos’ GDP.

With Laos, Chinese officials are trying to develop multiple solutions for the country’s debt problems with China, refusing to let another communist country fall. So far, China has been very generous allowing Laos to defer payments, but this can’t last forever.

China invested almost $1 trillion in developing nations over the past 20 years, and debt forgiveness to Laos would probably trigger many nations around the world to ask for the same. This is something China can’t afford right now, especially while it’s in the midst of a real estate and elevated debt crises.

China’s Debt Trap

In 2022, Fitch assigned Laos a long-term foreign currency issuer default rating of ‘CCC-,’ which indicates “substantial credit risk,” making default a real possibility. There’s no denying that the Lao government needs to seek debt service deferral and continue to refinance its existing debt stock. But the argument whether Laos was caught in a debt trap by China is still debated.

The huge cost of China-funded infrastructure projects like the Lao-China Railway and several hydropower plants support the theory that China has trapped the small country with debt. Despite this the Laotian President, Thongloun Sisoulith, argues Laos hasn’t fallen into a Chinese debt trap.

But given the strong connection between the two Communist countries, its not surprising that the President would reject claims that have been particularly popular in the West. Its worth noting that a study analyzing 100 contracts between Chinese state-owned entities and government borrowers found that Chinese contracts contain unusual confidentiality clauses that prevent borrowers from revealing the terms or even the existence of the debt.

The report also found that Chinese lenders seek advantage over other creditors through various methods and also use cancellation, acceleration, and stabilization clauses to potentially allow the lenders to influence debtors’ domestic and foreign policies. Altogether the confidentiality around these arrangements and other terms in the contracts could limit the sovereign debtor’s crisis management options and complicate debt renegotiation. Based on these findings, its easy to see how Laos has found itself in this geo-political and economic situation.

Even as the Laotian government tries to downplay suggestions that the economy is in trouble, it continues to evoke many comparisons to Sri Lanka — which declared sovereign default in 2022. However in Laos’ case, the chances of a default appear less likely given that China is unwilling to face the ramifications of such a default.

What this Means for Laos…

Perhaps it’s some sort of solidarity between the two communist governments that makes Laos refuse to diversify its foreign investment or receive help from any other country or global financial institution like the IMF. But, the Lao government needs to act fast and come up with a way to stabilize its economy and currency, or its debt will eventually snowball and become uncontrollable. If this goes on, Laos will risk becoming a vassal state of China, instead of its own, independent country.

The communist party in Laos should also find a way to increase the people’s faith in the country. In the past, people might’ve not liked or respected the communist party, but its economic achievements is what made it accepted. If it can’t bring back economic growth, then the government will never recover in the eyes of Laotians.

Disclaimer

Please visit and read our disclaimer here.